Friday, April 16, 2010

Begging For Pussy With George Clinton

Here's a piece I wrote for the awesome Buddyhead.com a couple of years ago; am reposting it here, inspired in part by the tragic death of journalist and screenwriter David Mills, who passed away unexpectedly at the end of last month, and whose excellent blog, http://undercoverblackman.blogspot.com/, contained copious evidence of his love for the whole Parliafunkadelicment thang.

“How you doin’? I’m pretty good… I’m ready for ya…”

The voice on the other end of the line sounds madd gravelly, and that’s not just several tonnes of transatlantic static coating his words in crackly fudge sludge, but several decades on the business end of a life spent as circus-master of a never-ending party, ever-engulfed in rubbery low-end, supine and snapping groove, and fuelled by more contraband substances than a piker like Scott Weiland could even name. George Clinton probably shouldn’t even be around right now – certainly, a number of his stellar sidemen, guest-stars in that Parliafunkadelicment thang, took it to the bridge one last time some years back – but he’s still alive. Very much so, in fact.

A few months back, I had the privilege of interviewing James Brown saxophonist Maceo Parker, the man whose hard-bop bleat burst out from between the whipcrack licks of Brown’s classic groups, and was later manipulated by the Bomb Squad into the blood-curdling siren-scream that wailed throughout Public Enemy’s ‘Rebel Without A Pause’. Following a number of combative tours of duty with Brown, in the late 1970s Parker took up with the only other artist who could reasonably challenge the Godfather for the Funk throne, signing on as musical director for Clinton’s Parliament. It was, he said, something of a culture shock.

“Where James preached uniformity, punctuality and discipline, George didn’t have any of that,” Maceo laughed. “And that was shocking, it really was. If some guy was into Tarzan, and wanted to dress onstage like Tarzan, or like a baseball referee, or a pilot, that was okay with George. I mean really, really okay. And if someone wanted to wear the same outfit for four years and not wash it, that was okay with George. I was used to tuxedos, bow ties, patent leather shoes… Uniforms. George said, life’s just a party, so you shouldn’t be uptight about how people dress. And that was his concept; they’re from outer space, and they’ve come down from their galaxy to show the people of Earth what funky music is really about.”

When I tell Clinton about Maceo’s reminiscences, he unleashes a deep, easy chuckle and adds, in the same booming baritone that preached of a forthcoming Armageddon over the opening bars of Funkadelic’s ‘Maggot Brain’, that “Funk is about the party. And funk is also whatever it takes. Do the best you can, and that’s funky.”

George’s muse wasn’t always such a kinky, freaky, polymorphously perverse thang. Born in Kannapolis, North Carolina in 1941, Clinton later moved North with his family to New Jersey, starting up his own barbershop, straightening nappy duds with pressing irons (as was the fashion at the time). Like many a young barber in the 1950s, Clinton also pursued a hobby in harmonising, forming his own doo-wop quintet, The Parliaments, in the image of his heroes Frankie Limon and The Teenagers. It’s a style he’s recently returned to, reuniting the members of the Parliaments – Ray ‘Stingray’ Davis, Clarence ‘Fuzzy’ Haskins, Calvin Simon and Grady Thomas, all of whom later served in Parliafunkadelicment – to cover ‘Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight’ for his 2005 album How Late Do U Have 2 B B 4 U R Absent?, and entering the studio earlier this year to record an entire set of doo-wop classics.

“I love doo-wop,” he begins. “It’s always fun… Whenever I made albums with Bootsy [Collins, gleefully flamboyant bassist who worked with Clinton and Brown, and also fronts his own Rubber Band], we always included a couple of ballads in there. When we got inducted into the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame, I bumped into the Young Rascals [soulful New Jersey rock’n’rollers from the 1960s], and we spent all day sitting backstage, singing doo-wop. I love doo-wop, because it’s all about begging for pussy! [laughs]”

I’m struggling to believe George Clinton has ever had to beg for pussy…

“Nowadays I have to beg myself to go get some!”

Clinton’s Parliaments later morphed into Parliament, scoring an early hit with ‘(I Wanna) Testify’, before shenanigans with their label Revilot (which declared bankruptcy, transferring their contract to Atlantic) saw Clinton can the Parliament name, forming Funkadelic with most of the same musicians. Indeed, Parliament’s debut album, 1970’s Osmium, was released the same year as Funkadelic’s eponymous debut, and shared that album’s slurring, carnal, mind-expanding sense of funk, along with a haunting, beautiful bagpipe-augmented ballad upon the subject of death, ‘The Silent Boatman’. Following a short period working as label Invictus’s in-house band (and cutting some killer tracks for The Chairmen Of The Board’s funkdafied final album, Skin I’m In), however, Clinton put the Parliament moniker to sleep for a while, and navigated Funkadelic towards the outer reaches.

The albums that group recorded throughout the early 1970s remain as crazed, as futuristic, as genius as they must have sounded upon release, a golden sprawl of loose booty breakbeats, thick wet wah-wah, ludicrous concepts and more than a little apocalyptic dread. The closing track off their 1971 album Maggot Brain, ‘Wars Of Armageddon’, was a case in point: its unhinged, echo-drenched ten minute hurtle through broken-glass grooves, screaming shape-shifting guitar, dubby FX, and pre-Hip-Hop ‘samples’ (of everything from shattering glass, to feline shrieks, to squabbling lovers, to gunshots, to that very Armageddon of which the title warns) warped the nascent genre of ‘funk’ as surely as Jimi Hendrix’s loving ax-abuse changed rock’n’roll forever.

“We changed up our style, right at the time when the European groups were coming over here,” Clinton explains. “We went ‘rock’n’roll’ as Funkadelic, we mixed Motown with rock’n’roll. That’s where the Temptations got it from; we were copying the Temptations at first, but once we got to ‘68, ‘69, they were copying us, with songs like ‘Cloud 9’ and ‘Psychedelic Shack’. They were imitating us by that time. We changed up, we never stopped changing, we stayed underground. By the time of Free Your Mind And Your Ass Will Follow [their 1971 sophomore LP] we had our own core of fans who dug what we were doing.”

Those fans weren’t just plugging into the noises Clinton and his gang of brilliantly twisted musicians were purveying [and the Parliafunkadelicment ranks would play host to a litany of dusted genii throughout their existence, including Bootsy, mercurial guitarist Eddie Hazel, and keyboardist and arranger Bernie Worrell, who would raise the group’s efforts to near-symphonic levels of lushness]. They were also buying into the Funkadelic mindset, Clinton’s lyrics and sleevenotes zipping across the whole crazy gamut of life, from birth to death, from love to war, encompassing multitudes. Maggot Brain, for example, may have opened with its mordant title track – a wrenching, epic guitar solo performed by an acid-dazed Eddie Hazel, and inspired by Clinton’s whispered instruction to “Play like your mother just died” – but its other six songs essayed love, drugs, cultural differences, drugs, Vietnam, drugs, and the aforementioned Armageddon. Indeed, the elliptical slogans that made up ‘Wars Of Armageddon’’s lyric sheet spoke eruditely of Clinton’s gladly-addled worldview: “What do we want? Freedom! Right-the-fuck-on, Brother! More power to the people! More pussy to the power! More pussy to the people! More power to the pussy! Right on, Right on…”

“Oh, you can’t take nothin’ serious,” laughs Clinton now, of such lyrics. “I try to tell people, I ain’t no guru, I’m just looking for some drugs and some pussy! I have my feet on the ground; if I pretended I was a guru, that would be bullshit. I didn’t know what I was doing really, they were just coming off the top of my head... Freestyling! That’s still how I write songs for the most part. Sometimes I’ll try and do something deliberate, pay attention and focus… But it takes so long! [laughs]”

1972’s epic double set, America Eats It’s Young, was perhaps Funkadelic’s most ambitious set yet, both musically and lyrically, reflecting an America torn apart by racial division, by the fallout from the Flower Power era and subsequent frustration and betrayals, by the Vietnam war (still raging on with no end in sight), and by the actions and pronouncements of President Richard M. Nixon, who would soon disgrace the country and leave office in shame.

“‘Wake up, live in the presence of your future’,” murmurs George down the phone-line, mouthing the chorus to the album’s closing track. “I remember writing those songs… That was the album where I really was trying to see if I had any brain cells left [laughs]. I’d been under the influence of psychedelics for so long, I thought, damn, I wonder if I can be ‘logical’ at all? On that album, there are so many songs and so many subject matters – unfortunately, the Vietnam war was on my mind...”

History seems to be repeating itself; the album’s messages and themes remain pretty key, thirty-five years later.

“History really does seem to be repeating itself,” he agrees, sadly. “We’re definitely living through 1968-69 all over again. I was planning on just chasing girls for the rest of my life, I didn’t know I’d have to be writing songs about war and everything again, you know what I’m saying? I never thought everything would be repeated so closely like it was before, I’d have thought we’d at least be up in space fucking everything up there by now. But we still here on this planet, making the same dumb mistakes, getting into wars we shouldn’t be in… I would much rather it was some Star Wars shit or somethin’, or making peace instead of war… Some kind of evolution…”

Funkadelic began to evolve themselves, in the mid-1970s, as George and his musicians ‘changed-up’ again, and the Parliament brand-name roared into life once more, with 1974’s Up For The Downstroke LP. With Funkadelic signed to the Detroit-based Westbound label, Clinton took the ground-breaking step of signing those same musicians, under the Parliament moniker, to Neil Bogart’s Casablanca Records; a couple of decades later, the Wu Tang would attempt a similar hijack of the label system, each rapper signing to a different label for their solo careers, though such shenanigans would cause George many headaches as the 1980s began.

While Parliament boasted similar musicians, their musical identity was pronouncedly different to Funkadelic’s; where that band’s ethos was best expressed by the rhetorical question “Who said a funk group couldn’t rock?”, Parliament played to a tighter, more soulful groove, with horns and synthesisers and hooks and an appreciation for the dancefloor which anticipated the coming of Disco.

“We started adding the horns with Parliament,” remembers Clinton. “A whole ‘nother sound incorporated within Parliafunkadelicment. A lot of people didn’t know we were the same group… We’ve snuck around behind ‘em two or three times [laughs]. They didn’t know it was us!”

You liked to keep people on their toes…

“Yeah, I love it. It keeps me young. And I love trying to keep up with music, like I said, to find the music parents hate. Whatever young musicians come up with, that the parents hate, that’s always the new thing, and that’s what I start making. Same with ‘Atomic Dog’ [from Clinton’s 1982 solo album, Computer Games, his first following the end of Parliafunkadelicment as recording entities]…”

As the 1970s wore on, Clinton’s two groups continued to record and tour apart from each other, building a brilliantly schizophrenic canon of billowing funk and graceful groove. The summit of their achievements, perhaps, was 1976’s P-Funk Earth Tour, an elaborate touring stage show featuring ‘both’ groups performing a set of Parliafunkadelic favourites. The most memorable moment of these shows, however, was non-musical. Bringing to life the sleeve artwork of Parliament’s 1975 smash album Mothership Connection, a huge prop star ship would slowly sink from the roof of the venue, landing upon the stage where Clinton, as his alter ego Dr Funkenstein, would clamber out and begin performing.

“That was phenomenal,” he remembers, still a little awed at the memory. “We’d rehearsed for a long time. Having watched Pink Floyd in the early days, and The Who doing Tommy, and the musical Hair – which also copied us – we ended up doing a semi-serious spoof of all this stuff. When we did the Mothership shows, I had the whole concept mapped out: Pimps In Space! [laughs]”

In some ways, the Mothership Connections Parliafunkadelicment achieved onstage during this era were their high-point; as the 70s gave way to the 80s, contractual problems with his labels and pay disputes with his musicians saw Clinton retire Parliament and Funkadelic, to pursue a solo career, along with occasional tussles with the law over substance-issues. Thanks to the samplicious ways of the Hip-Hop generation, however, the classic grooves of Parliament (and, to a lesser degree, those of Funkadelic) never fell from favour and, he says, Parliafunkadelicment were recently approached to perform one of their Mothership Connections in actual, proper Outer Space… “We were supposed to perform on the space station, in 2005,” he promises. “We were ready to go and everything… Zero-gravity funk… Anti-matter music…”

Instead, he’s remained earthbound, continuing to bring funk to the masses, keeping that party from ever ending. Though it might surprise you to learn that George Clinton is actually himself something of a wallflower…

“It’s all about the stage for me,” he chuckles. “I’m actually a bit of a fake when it comes to the after-show party. I like to take my ass home early. All the P-Funk fans, they mostly expect more than I can give… I know I can’t live up to the expectations they’ve built up about me over the years! And the ones who come along and want to have sex with me? I’m scared of them…”

(c) Stevie Chick, 2010

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

Arthur Russell - Wild Combination

Wild Combination: A Portrait Of Arthur Russell

****

PLEXIFILM

Warm and insightful documentary traces the beguiling apparition that was Arthur Russell

Due to the scant availability of interview footage with Wild Combination’s notoriously shy subject, Arthur Russell seems ghostlike even in this documentary dedicated to his short life and voluminous works; there, but not there. Director Matt Wolf nevertheless evokes the late composer/cellist assuredly: through the words of his family, friends and peers, still photographs and flickering passages of live performance, and, most of all, his music, Russell haunts every frame.

There was always something spectral, something haunting about Russell’s music, this quality uniting a body of work that embraced such divergent strands as Avant Garde composition, introspective and fragile folk song, and ecstatic, trance-like early Disco. Born and raised in the rural wilds of Iowa, Russell was a sweet-hearted, acne-scarred misfit curious about drugs and alternative lifestyles, and consumed by music. Aged sixteen he moved to San Francisco at the dawn of the Hippy Age, beginning a journey that would draw him to New York City, and the subterranean poetry and experimental music scenes. Of seeing Russell perform for the first time, sometimes collaborator Allen Ginsberg recalls here, in footage from Russell’s funeral, that he was “like William Carlos Williams, but he sings.”

Russell thrived in New York, spending his nights working as musical director of The Kitchen – the Greenwich Village artspace located within the Mercer Arts Center – or at David Mancuso’s hedonistic and joyous Loft parties, where Disco first stirred. This breadth of creative focus perhaps both explains Russell’s relative low profile during his lifetime, operating within the experimental fringes of underground art and music, and also why his music has developed such a swarming following in the years after his death. “How could one person work in all these different ways?” ponders musicologist David Toop, one of the movie’s talking heads. “Not many people allow themselves the full extent of their complexities.”

Wild Combination conjures up a man alive with brilliant ideas – friend and early collaborator Phillip Glass remembers Russell’s dreams of composing “Buddhist Bubblegum music” – but the narrative’s turn for the tragic, with Russell’s positive diagnosis for HIV, shifts the documentary into more emotional territory, which Wolf handles with tender skill. Tom Lee, Russell’s partner since 1980, paints the man behind the music as “the person I wanted to end every day with”.

Most haunting is the footage of Russell performing late in his life, already visibly ravaged by AIDS, but still able to pluck beauty from a cello, an echo pedal and his warmly unguarded voice. “His gifts were increasing, as his strength was leaving him,” notes one friend, but the movie also traces the rebirth his music has enjoyed of late, thanks to the efforts of Steve Knutson of Audika Records, releasing unheard Russell music and curating his legacy from Tom Lee’s vast collection of tapes.

The final moments of the movie find Lee discussing the comfort those cassettes give him today, smiling at the sound of Russell’s voice, a fitting close for this affecting exploration of ghostly magic.

(c) Stevie Chick 2009

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Les Savy Fav

Tim Harrington leans back on a metal folding chair, crazed gesticulations possessing his hands, midway through the latest in a series of unlikely tales. His eyes are wild, like his thick, curling-at-the-edges brown beard, or his bedhead-of-all-bedheads blonde hair. His monkish frame clad in pastel shades, he looks like a character from Caddyshack – Rodney Dangerfield’s gregarious and gently-unhinged boho art-punk side-kick perhaps – who ended up on the cutting room floor.

Right now, he’s talking about Locusts.

“Do you get locusts here? They appear, like, once every eight or thirteen years – you see ‘em, clinging to the trunks of trees – and they eat everything in sight.

“I’ve been a locust,” he grins.

You have?

“Yeah, for a Public Service Announcement, in the States. They made me this cool costume and everything, and filmed me hassling people, stealing food from ‘em, getting in their faces. Then the voice-over comes: ‘In America, locusts are annoying. In Africa, they’re KILLERS!’

“It was such a cool costume, I really looked like a locust! I wanted to keep it, but when I mentioned this to the production company, they started talking about me taking the costume in lieu of my fee. And I wanted to get paid.” He sighs. “It was fitted for me, and everything.”

Were I a lesser writer – and who knows, perhaps I am – I would now be drawing a painful parallel between the Locust, one of nature’s hardiest of tiny beasties, and Les Savy Fav, the group with whom Tim has howled, cantered and caterwauled for twelve or so years now. After all, the group have pursued a singular, solitary path through underground rock for that decade-and-change, evading trends and scenes while making a twisted, flailing, melodic and concise noise all their own. Always eager to ditch a bandwagon at the earliest occasion, they went on ‘hiatus’ earlier in the decade, just as the New York art-punk scene they’d helped pioneer started to explode.

“I guess it all started to feel like a career,” says Syd Butler, Les Savy Bassist and honcho of French Kiss Records, the label the group have released their music on since their second album, 1999’s The Cat And The Cobra. “And we never wanted it to feel like that. We wanted to make the music for its own sake.”

“We had other ambitions we wanted to fulfil,” adds Tim. “Syd wanted to concentrate on the label, I wanted to focus on design for a while… I basically didn’t want to end up a Successful 40 Year Old Rock Star and feel like I’d wasted my life, y’know?” he laughs. “Sitting there by my pool, thinking, ‘I wish I’d pursued my passion for design’. Seriously, I’ve always had nothing but respect for professional musicians, people who play music and make their living from it their whole lives. But we wanted to do other things, too.”

The hiatus was signalled by drummer Harrison Haynes’ move away from New York, but has – as the group’s excellent new album, Let’s Stay Friends, and their triumphant appearance at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival attest – proved temporary, the lure of Les Savy Fav proving irresistible. As well it might; the stage is clearly somewhere Tim Harrington belongs.

I still remember the first time I saw Les Savy Fav, at 93 Feet East, February 13th 2001. The date sticks in my mind, because…

“It was Valentine’s Eve,” interrupts Tim. “Y’know, how All Hallows’ Day, Saint’s Day, is preceded by this messed up holiday, Hallowe’en? I thought Valentine’s Day could do with a similar event the night before, turning it all upside down. Valentine’s Eve.”

According with this new tradition Les Savy Fav wished to inaugurate, Tim garlanded the chill, cavernous 93 Feet East in hearts he’d fashioned from the pages of the hardest-core pornography. To accent the evening, if you will.

“I’m a renowned collector of vintage niche pornography,” interjects Tim. “In New York, I’m like the only guy who has a complete collection of original editions of Oui magazine, 1972-1981, in mint condition. And also Leg Work, which is a harder magazine to collect. There are all these extra editions, Leg Work Black, Leg Work Latina…”

While the three musicians in Les Savy Fav skulked purposefully in the shadows, stirring up a noise of slaloming, jagged, haywire riffs and neon blasts of perverse pop, Tim took to entertaining his audience. First, he was tearing porno-hearts from the walls, forcing his tongue through paper vaginas, just stone waggling it. Next, he was climbing the amps and gear and clumsily clambering onto a huge speaker suspended from the ceiling by girders and steel chains, swinging it violently as he sang, a good fifteen feet above the ground. Finally, he returned to the stage, dismantling the drum kit and walking off with a side-tom which he proceeded to beat, like some deranged leprechaun drum-major, leaping into the audience and completing a circuit of the auditorium. Such behaviour fair blew the mind of the audience that night. It was, however, just another abnormal night for Les Savy Fav.

“It’s like a kind of surrealism, being an adjunct of the music,” explains Tim, of his onstage performance. “The way the group plays, a lot of it is improvised – the songs have their sections, but they’ll extend them or shorten them, keep it fresh, different. And all the stuff I do, it’s all part of the same thing, so every show’s different, so we don’t ever fall into a rut, so it stays interesting, for us and for the audience. We want every show to be special.”

What’s the wildest it’s gotten?

“Oh, there are so many stories… There was this one time, some friends gave me this huge plush toy dog they found in a thrift store as a present. It was as long as I was tall, so I ended up cutting it open and pulling all the stuffing out. The next night, the band started playing, and I got inside the dog, like it were a costume, all ready to run onstage. But things started to go wrong – the guitars were out of tune, it wasn’t quite happening. And as I made for the stage, I realised I hadn’t cut any eyeholes in the dog costume, and ended up stumbling over. It wasn’t good. We kind of cooled off on costumes after that show.”

The members of Les Savy met just over a decade ago, while studying at Rhode Island School of Art, an institution heavy with punk rock kudos. “Talking Heads were from there,” nods Tim. “Lightning Bolt also. We played our first shows with those guys in the audience. I was born in New Jersey. I loved it there, but from the age of ten or eleven, I knew that I wanted to go to art college. It was just somewhere I had to go.”

This artistic bent continues through Les Savy Fav, not just from the disjointed twists and conceptual swipes of their records, but also in the design of their tee shirts, their album sleeves. Their debut LP, 1997’s 3/5, was an art object in of itself, the disk contained within the packaging of a shower cap. They want every show, every release, not just to be the latest in a stream of product, but special in of itself; this is why they could never see music as a ‘career’, why they’ve absented themselves from the indie-rock treadmill, in favour of doing their thing at a pace that suits them. The Game is not one they want to play.

“I worked at a major label for a year,” offers Syd. “It was sickening, guys in the A&R department receiving insane pay-packets and doing nothing. There’s a concept of ‘failing up’ in operation… As the owner of a small record label, I can say that the industry is fucked. Especially thanks to the internet, there’s a generation of kids who have no problem with stealing music, who think its okay…”

“We set up an ‘honesty jar’ on the merch table on our last tour,” smiles Tim. “’If you downloaded our album for free, please donate’. We got some money!”

It’s the small victories that keep you going, and Les Savy Fav keep going. Let’s Stay Friends opens with ‘Pots And Pans’, an anthemic ode to a group who “made a noise no-one could stand”, but who play anyway, because “this tour is a test”. It’s about standing up and making your own noise, your own art, to express “a human heart that’s nowhere near its end”. Tim blushes a little when I mention the lyric, asking if the words are autobiographical.

“I played the song to a friend who worked on the album, saying, the words are just kind of a joke, about this imaginary band. And he listened to it, and he said, ‘Uh, no they’re not’. And you know what?” he grins. “I guess they’re not.”

(c) Stevie Chick 2008

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Metallica

Fall Out Boy 2008

When Rock Stars Attack

Friday, October 03, 2008

The Heads

The Heads

Dead In The Water (Rooster)

Despite possessing such a deep love for noise bestowed with heavily

psychotropic effects, I've always felt something of a fraud when

writing about psychedelic music, having never personally dropped

anything stronger than a couple of valerian to ease jetlag. And yet,

I've been familiar with the relationship between contraband chemicals,

mind expansion and screaming skronk rock since the first time my Dad

played me Led Zep's 'Whole Lotta Love' and relayed in an instructional

manner, over the freeform guitargasm middle section, reminiscences of

listening to it while sprawled on the floor, between two huge

speakers, while blitzed on some illicit chemical during the halcyon

Sixties. As I was but eight years old at the time, he added a hasty

"hey kid don't do drugs" by way of a coda, and that was that.

But while my third eye has remained un-squeegied in the interim, the

magickal sounds of feedback, drone and phaser asphasia have ever

jolted my grateful brane, from my earliest pre-teen experiments with

such lysergic compounds as Hendrix and The Byrds, through subsequent

addictions to the Buttholes, Sonic Youth and Comets On Fire. This

latest slab of joy from Bristolian noisenik perennials The Heads is

certainly one heavy hit of something, a disorientating and uncut blast

set to send synapses sprawling and throbbing, administering most

pleasant bruises to the aural tender spots while a wicked light show

plays on in the foreground.

Over seven or so albums thus far, these hardy druganauts have

performed a graceful devolution, from stellar riffouts sucked into Far

Out vortices and strewn with funhouse-mirror vocals, to releases such

as this, edited from endless rehearsal jams into a mind-pummeling

symphony in four movements. The titanic riffs that first won them love

from the global stoner rock constituencies are still present, but now

freed from earthbound song structure, materializing from pools of

fugged din to build and build until they collapse into the electric

murk, to be followed by similar such behemoths. Dead In The

Water brings to mind Comets On Fire's stated intention, of

capturing those peak moments of inspiration heavy rock titans pepper

across their works, and stretching those moments over entire songs,

albums, their discography in fact. Similarly, The Heads here trade

structure for a joyous indulgence of the wonders that screaming

oscillators, acid-scarred guitars, monolithic bass and

atom-splintering drums can evince, when pushed to the absolute fuckin'

max.

Fans of Comets and Acid Mothers Temple will grok this riot in the

blink of a dilated eye, but the strongest comparison for these

inspired trips are the Complete Sessions box sets for Miles Davis's

Jack Johnson and On The Corner LPs, in the way the tracks

brilliantly vault the trap of formlessness for, instead, a fearless

freeform-ness, these epic and frazzled narratives switching from peaks

of freaked drama to passages of pearlescent drone and full-spectrum

sonix. Stitched together by snatches of pointedly trippy dialogue,

Dead In The Water comes on like some psychedelic horror flick,

where you're never sure what mind-scrambling phantasm is about to tear

from the speakers. Riding wah-pedals into the sun, sending shards of

cymbal flying like shuriken, chasing some spiral riff charting a path

to sublime Nirvana, The Heads hold the listener entirely under their

control, so their screaming noise would leave even the Straightest

Edge entirely stoned. If this is a trip, then I'm loving it.

(c) 2008 Stevie Chick

Friday, July 18, 2008

Jesu / The Bug

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Saturday, March 01, 2008

Thursday, January 10, 2008

The Monks

THE MONKS are like The Velvet Underground of the garage-rock scene – few bought their sole album, Black Monk Time, on its release in 1966, but the group have since become an influential rock’n’roll cult. American GIs stationed in Germany, the Monks infamously shaved their crowns and wore only black onstage, but it was the primal invention and off-kilter psychotic quality of their music, echoing the violence of Vietnam and the tumult of the 1960s, that ultimately won them subterranean fame.

Tonight, four decades after they split, they played their first-ever

Their songs remained as gloriously, electrifyingly odd as before, from incessantly catchy rave-ups like ‘Oh, How To Do Now’ to an unhinged ‘Shut Up’, its call-and-response chorus chanted by an audience young enough to be the Monks’ children, who discovered the group via namechecks from fans like Jack White. Moved by the response, frontman Gary Burger promised a return to these shores next year. An official documentary, The Transatlantic Feedback, is set for release next year, but tonight proved The Monks are no mere museum pieces. No, they’re still crazy, after all these years, and long may they rage.

(c) 2007 Stevie Chick

Wednesday, January 09, 2008

Saturday, December 01, 2007

Maceo Parker

[for Plan B magazine; meeting Maceo was, as you might imagine, quite a trip, and he was one of the coolest interviewees I've ever had the pleasure of questioning. Long may he blow...]

He was, and perhaps still is, the hardest working saxophonist in showbusiness, blowing horn and evading fines with James Brown over several stretches through the 60s, 70s and 80s. Maceo Parker lent his furious bebop bleat to Brown’s 1973 studio masterpiece, The Payback, and played on his epochal 1968 single ‘Say It Loud (I’m Black And Proud)’. Say It Live And Loud, a highpoint amid Brown’s blizzard of live albums (taped the night after Brown recorded his black power anthem, but unreleased until 1998) is as blistering evidence as you could wish for of Parker’s crucial place within Brown’s onstage sound, while anyone au fait with 1980s Hip-Hop will be familiar with the sound of Maceo’s horn, turned inside-out thanks to nefarious manipulation by the Bomb Squad, squealing like the devil’s own siren throughout Public Enemy’s ‘Rebel Without A Pause’.

Stepping off the JBs train, he led his own group, before hooking up with George Clinton to usher in the high times of disco-era Parliament. In the 1990s, he graced De La Soul with his presence for their Buhloone Mindstate album, signed up with another mercurial funk genius blowing for Prince’s New Power Generation, and guested with Jane’s Addiction and the Chili Peppers. Today, he’s promoting his latest album Roots & Grooves, a double set featuring a brace of hard-funk licks sharp enough to belie his 64 years, and an album’s worth of Ray Charles covers backed by an 18-piece Big Band from

Covering Charles’ songs is for Maceo very much a tribute to his roots, growing up in

His mother had, he says, “a great voice. She could have been a star, but she chose singing religious music over nightclubs. I was telling her on the telephone today, that she could’ve been Ella Fitzgerald if she’d wanted to be; she’s 80-something now, but she still has a great voice.” Both parents attempted to learn the piano but quickly dropped it; the instrument remained in the Parker house, however, and so-inclined visitors would often tinkle the ivories, with Maceo gazing on in rapt concentration. “I’d watch their fingers,” he says, “really watch them. I musta been six or seven years old, but I’d remember the fingering, where the chords were. And when the grown person would get up and start talking to ma, I’d go and start playing the song. I didn’t know how to play the piano, but I was playing the piano!”

Parker describes his time with James Brown as being “like a train ride. You get onboard, and once it’s taken you as far as you want to go, you get off.” Maceo had plenty of preparation for his first embarkation, having formed a group with his brothers Melvin and Kellis when he was eleven. “My uncle had a group, the Blue Notes, and we tried to play everything they played. We tried and tried and tried, and eventually we got to a point where we could play three or four of my uncle’s tunes, and people could recognise what they were! We called ourselves the Junior Blue Notes, and began playing around town, and people we’d never met before started saying, ‘Wow! You can really play!’ That’s when we knew something was happening.”

The Godfather of Soul caught one of the group’s performances some years later, and was particularly impressed with the drummer, Melvin, offering him a place in his group. A year later, Melvin was drumming for Brown, having also secured a slot for 21-year old Maceo, for whom the opportunity offered the chance to fulfil a long-held dream. “I’d always wondered, what would it be like to walk into a bar somewhere you’ve never been before, throw a quarter into a jukebox, and hear yourself play? I knew that, playing with James Brown, we’d get to record in a studio. By the time it finally happened, it wasn’t the thrill I thought it was gonna be,” he laughs, of his jukebox fantasy, “but I was a little more grown by then, and my dreams had evolved to playing stages all over the world.”

This was another dream playing with Brown would facilitate, but the Godfather was an exacting boss. “All the stories you’ve heard are true,” Maceo chuckles, “but it’s all to make you better, to make the group better. James preached discipline, decorum, taking pride in how you dress, trying not to perform in uniforms that look like you just slept in them, just being proud of who you are and holding your head up high. Again, you’re aboard the train, and it’s taking you where you need to go, you have to trust in the driver. That’s how I viewed working with James: anyway he wants to do a thing, that’s how I’ll do it.”

A year after joining Brown in 1964, Maceo was drafted into the military, returning afterwards for another three year stint, during which the Godfather was greatly accelerating the evolution of this thing we call funk. Shortly after recording a feverish homecoming date in Atlanta, GA in 1969 (which the Godfather intended to release as James Brown At Home With His Bad Self), however, Maceo exited Brown’s employ, accompanied by the rest of the group.

“We had grievances, it was time to tell the conductor to stop the train,” remembers Maceo. “The other guys got wind that I wanted to leave, and suggested we all approach James en masse, and threaten to quit. And James didn’t like that, it was too much power for him; later on, in his book, he said he fired me, but he didn’t. I’d not wanted the rest of the band to quit, though; I wanted to look James in the eye and let him know I had enough, uh, whatever, to quit on my own.”

Brown didn’t look far for replacements, hiring a couple of young kids, Bootsy and Catfish Collins, who were always hanging around his recording studio in Cincinnati as the backbone of his new backing group, The J.B.s. The transition was signalled with 1970’s Sex Machine album, where a J.B.s-era late night session, which yielded the hugely-successful titular track, was cobbled together with the 1969 Atlanta show as a live album, with canned studio noise covering the cracks. The J.B.s would not last long, however. “Bootsy and Catfish had joined, thinking they’d get to play with us,” laughs Maceo. “Then when they arrived, and discovered us gone, they started to wonder what had made us quit. And then they found out…”

Maceo, meanwhile, had gone on to form a new band with his old colleagues, Maceo And All The King’s Men, their moniker perhaps a jab at their erstwhile King Of Soul employer. “We had fun,” Maceo remembers. “Some nights we wouldn’t make more than $80 between all of us, but that was just enough gas money to get us to the next show. We were young, we had no responsibilities, what did it matter?”

Parker would return to the Godfather’s employ during the 1970s, leaving again to work with George Clinton, as Musical Director for Parliament. Though

“And that was his concept; they’re from outer space, and they’ve been assigned to come down from their galaxy to show the people of Earth what funky music is really about. We had a tune called ‘Atomic Dog’, and George would tell the audience, I gotta find me a dog! He’d walk around the stage, and pluck a girl from the audience, throw her down and walk her like a dog…”

Did you find this hard to adjust to?

“No. It took a minute to adjust... There were some real funky players in that group, like Eddie Hazel. He was funky, and funky is funky. [mimics funk guitar] And you appreciate it when you hear it.”

In the years that followed, Maceo returned to the Godfather’s bosom a couple more times, fielded offers for high-profile collaborations, pursued several solo projects, and has been blowing horn for Prince since 1999’s Rave Un2 The Joy Fantastic. And he finally got his chance to play with the Collins brothers, as a member of Bootsy’s Rubber Band, throughout the 70s and 80s.

“Bootsy had a little of James’s uniformity, but also a little bit of the George Clinton thing too,” says Maceo. “We didn’t get as raunchy or vulgar as George, but he’d hint on a little something every now and again. And, like George, he loved flashy clothes, in particular anything that was red and white. Nobody else can play like those two, I’m sorry. [mimics interplay of the Collins brothers] It’s nice.”

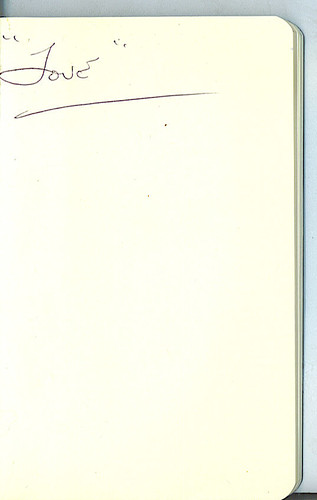

At the end of the interview, Maceo asks if he can borrow my notepad and pen and, on the next available blank sheet, scribbles a word in a neat scrawl near the centre of the page. He then pushes the notepad back across the table.

“I just want you to know, everything I do… Everything…” He draws his hands up to his chest, which rises slowly as he takes a deep breath, filling lungs that have blown like the proverbial hurricane through the histories of funk, soul and pop – a gesture which unconsciously reminds just how grand an ‘everything’ that really is. “…is because of this.”

The word is “love”.

(c) Stevie Chick, 2007Thursday, November 01, 2007

Brian Wilson

September 12th saw Brian Wilson return to the freshly-refurbished Royal Festival Hall – where he had previously debuted Smile and Pet Sounds – for the world premiere of his newest work, a song-cycle written with Wondermint Scott Bennett and long-time collaborator Van Dyke Parks. Entitled That Lucky Old Sun (A Narrative), conceived while Wilson was “in the middle of a real creative trip”, it is a musical tribute to Southern California, a location enshrined in so many Beach Boys songs.

In typically excitable, enthusiastic mood, dressed in a black and white striped top and accompanied by his ten-piece band and the Stockholm Strings And Horns, Wilson treated his audience to a joyous opening set of Beach Boys favourites from ‘Surfer Girl’ to ‘Heroes And Villains’, slipping in a snippet of ‘That Lucky Old Sun’ as a tease; that the audience were clapping along by the fifth bar was an encouraging sign.

Following a twenty minute interval, Wilson and his musicians returned to perform the nine songs of That Lucky Old Sun, with periodic interjections from Van Dyke Parks’ dippy, loving, poetic narration, accompanied by projected animations. Brian’s most ambitious new work since returning from the wilderness, the song cycle recalls Pet Sounds and Smile, not least in its playfully baroque arrangements – a playground riot of glockenspiel, tympani, strings and harmonies all played with a smile – and melodic nods to the Beach Boy canon, complementing the autobiographical bent of the lyric-book.

That Lucky Old Sun revisits familiar

‘

(c) 2007 Stevie Chick

Sunday, October 28, 2007

juggle tings proper

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Thursday, September 27, 2007

Fall Out Boy

“EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

The high-pitched banshee wail is ear-piercing and nigh unbearable. We’re at Nellis Air Force Base in Clark County Nevada, North East of Las Vegas, where the majority of the US Air Force log their hours of fighter pilot training, a location that has weathered the arcing screams and sonic booms of modern jet airplanes since opening in 1941.

But this isn’t the airstrip, rather an on-base department store for local military personnel and their families. And that incessant shriek isn’t the sound of burning jet fuel and whirring turbines, but hundreds of young kids, mostly girls, assembled for a meet’n’greet signing session with their idols, Chicagoan pop-punks Fall Out Boy, playing the Palms hotel in Las Vegas later that evening. As the group sit behind a long table piled high with promotional posters, idly toying with sharpie pens, armed Military Police dressed in camo-garb manage the crowd, barking at them to stand behind the grey plastic shopping trolleys banded together like some crude velvet rope. Beatlemania was never like this.

Or perhaps it was. The group’s tour manager Charlie, a towering, shaven-headed dude who looks like a squaddie himself, yells at the slowly-moving line that “Only one item per person will be signed”; the (mostly) girls file past, bringing with them CD sleeves and promo photos and even a couple of guitars to be signed by the group. More precious even than the autographs, however, is the fleeting personal contact with their heroes, and bassist and chief heart-throb Pete Wentz in particular.

“He told me that he liked my hair and my face!” screams one hyperventilating nine year old to her mother, signed poster clutched to heaving chest. “Oh! My! God! Pete said ‘What’s up?’ to me!!” yells another pre-teen hysteric, like the greeting could cure cooties. Only a dead-hearted cynic could remain unmoved by such unabashed devotion, however unsettling it might initially seem.

“They’re reacting in the way they’ve been programmed to,” Wentz explains later, indulgently and a little bashfully, of such Beatlemanic scenes. “They only know you through MTV and the photo in the CD booklet, so when they actually meet you it blows their mind. I ‘get’ it, because that enthusiasm is what allows you to keep making music.” Still, the meet-and-greets take their toll; Wentz’s right hand, currently decorated with a deep red scar as a result of an onstage mishap, has suffered enough from crushing fan handshakes that he now offers his left out of habit.

The 200th fan having collected her poster, the signing session is ended with appropriately military precision, Charlie shepherding his boys towards the exit, the MPs dispersing the crowd. As the Fall Out boys scurry past the blouses, skirts and bras of the ladieswear section, fans disobey the soldiers’ commands and run after them, one desperate mother materialising from behind a rail of petticoats to snap Pete on her camera-phone. “Smiiiile for my daughter!” she howls, as Charlie runs interference and the group disappear through the doorway, to a USAF van waiting with its engine running outside. Welcome to a ‘typical’ day in the life of Fall Out Boy.

“When things like that become totally ordinary in your life, it changes who you are as a person,” muses Wentz moments later, as the group speed along to the Palms Hotel, and the next of their promotional commitments. He’s typing endlessly on his Sidekick; tonight’s support act +44 (fronted by Mark Hoppus, formerly of multi-platinum pop-punks Blink 182) have had to pull out, and Wentz is trying to organise last-minute substitutes in the form of Panic! At The Disco, a

Sat behind him, Patrick Stump, Fall Out Boy’s singer/guitarist, pores over a package handed to him earlier by a fan, a folder containing a gift for each member of the band. “Look, she did a painting each for all the other guys,” Stump frowns, indicating three surreal watercolours enclosed, “and they’re real good. And I got a sheet containing parody lyrics for one of our songs.”

Patrick lifts up his ever-present baseball cap and ruffles the mop of butterscotch hair hidden beneath. While he sings all the group’s songs, and indeed writes all the music, it’s Wentz, the bassist and lyricist of the group, who’s considered the ‘frontman’. Where Wentz is kohl-eyed and olive-skinned, with an easy and infectious grin that doubtless glows in the dreams of his many fans, Stump is, by his own self-deprecating admission, not exactly a heart-throb. “I’m a totally normal guy,” he smiles. “I’m what we call ‘TV Ugly’, where I’m handsome enough to be cast as the ugly friend. I’m ‘TV Fat’, a ‘thin’ guy compared to most of the population, but, well, you know...”

Stump doesn’t envy the attention Wentz ‘enjoys’ from the media, focussed as it is on his puppy-dog looks, his relationship with pop singer Ashlee Simpson, and the more turbulent corners of his private life. “It’s strange, the person they sometimes make Pete out to be,” puzzles Stump. “I know him as good as anyone’s gonna know him; the guy I’ve read about is a dick, but he has nothing to do with Pete Wentz.”

Certainly, Wentz has endured a rocky ride through stardom, ever since the group’s major label debut, 2005’s From Under The Cork Tree, made them an ‘overnight success’ on their third album. The group formed in

Signed to Island records for From Under The Cork Tree, the album’s lead-off single ‘Sugar We’re Goin’ Down’ – a confection of anthemic punk-rock riffage, sugary harmonies and the kind of perfect-pop hook that imbeds itself in your brain without mercy – was soon an MTV smash, ensuring the album sold 68,000 copies in its first week (eventually going double-platinum) and delivering the group to the ever-rabid audience of hit show Total Request Live, typically stomping grounds for unabashed pop acts like Britney and Justin. It was a weird environment for a punk-rock band from

“I don’t think any of us anticipated any of this when we formed,” deadpans Stump, of the promotional activities their fast-won celebrity demands. “I was brought up on punk rock. I’d go to shows, and when a band starts playing people rock out, and when the band stops they go and have conversations, and the band walks offstage unhassled. You love the bands, but you could give two shits about the guys who play in them. And so, the first time someone said ‘hey, will you sign this album?’, I said ‘but I’ll get marker pen on it and ruin it!’”

It was Wentz who was to feel the public gaze most keenly, especially when naked photos of the bassist, shot on his Sidekick and sent to a possible romantic conquest, leaked onto the internet in March 2006. “I’ve been so candid in the past, and its burned me,” Wentz blushes. “I used to speak without a filter, but I ended up in hot water.”

This troublesome honesty wasn’t just limited to Wentz’s sex-life; he was also candidly open about struggles with his emotional health and his experiences with anti-depressants, a rollercoaster that ran at perilous speed throughout the making of From Under The Cork Tree.

“I can barely remember those years,” he grimaces, settling himself on the sofa of his tourbus, rough-housing with touring companion, gorgeous one year old bulldog Hemingway. “I was taking prescription medication; I was definitely a Drugstore Cowboy, mixing this with this, seeing what the combinations did. I couldn’t picture myself in two years. People would ask, what are you going to do on the next record? And I’d say dude, I can’t even see myself being alive.”

It’s a common story for kids of Wentz’s generation, prescribed anti-depressants at an early age, upon which they soon become reliant;

A near-fatal overdose on sedative Ativan early in 2005 inspired From Under The Cork Tree’s key song, ‘7 Minutes In Heaven (Atavan Halen)’, though Wentz says today, “I’ve never described anything that happened to me as a ‘suicide attempt’. But I thank God for my bandmates every day, for their tolerance. I was completely self-aware of the situation I was in, but I didn’t care enough to do anything. The guy who doesn’t know what he was doing, you can’t blame him, he doesn’t know. But the guy who knows it, and is just sitting there putting himself through it, you’d hate that guy. And that’s who I felt I was. In

Wentz’s emotional turbulence provides much meat for his songwriting, penning lyrics that balance a scarringly confessional bent with a penchant for wordplay; sample song titles include ‘Don’t You Know Who I Think I Am’, ‘Champagne For My Real Friends, Real Pain For My Sham Friends’, and ‘I’ve Got All This Ringing In My Ears But None On My Fingers’. Like all the best pop, Fall Out Boy play adolescent conflicts out as high drama, Wentz’s lyrics allied to riffs and melodies surging with an emotive dynamism, penned and sung by Stump. “It’s like he’s writing confession, and I’m singing it,” laughs Patrick. “I’m like a priest to him that way. He gets to say it through me, and I get to absolve him.”

The lyrics speak to a generation similarly anxious and disturbed, finding succour in songs awash with anguish; but Pete says he doesn’t have answers. “People come up to me and say, ‘Your band saved my life’… I still haven’t figured out how to react to that. Because, yeah, this band saved my life too. Honestly, I feel like one of the last people who should be giving advice to anyone about anything. I’m not the Doctor Phil of punk music.”

Patrick Stump reckons he was about eight or nine years old when music began to take over his life. “My parents had divorced, and I was helping my dad move his stuff out,” Stump remembers. “I was confronted by this vast record collection. I was a little guy, I couldn’t manage a whole box of vinyl, so carried them record by record, asking my dad about all these albums as I went along.” Stump’s father was a singer/guitarist in a local group through the 1960s and 70s, with a record collection swollen with rock, blues and jazz. “He had Herbie Hancock records, and Eddie Harris records, and he really loved Van Morrison. It was the blues and jazz stuff that really got me into music. Then I became a Prince nerd, and really got into David Bowie. Now, I’d say hip-hop is probably the music we as a band all love the most. I know that’s a strange thing for a dude in a rock group to say.”

Sat on the corner of the double bed that swamps his room at the back of the other Fall Out Boy tourbus – an array of baseball caps hanging on pegs from the wall, his dapper onstage trilby perched upon a hat stand by the bedside – Stump explains that the group’s latest album, this year’s Infinity On High, was written “with a chip on my shoulder. People told us that we were making music for fourteen year olds, and I took it as a compliment; when you’re fourteen, you’re not tainted yet. I’ve been one of those totally arrogant, idiot rock snobs in my time, but if you’re an artist it makes for bad art.

“I woke up one morning in a

For the album, these fledgling pop celebrities collaborated with both Jay Z and R&B legend Babyface. “It was great working with Babyface,” smiles Stump. “He almost doesn’t have to do anything to make you play better, you just walk into his studio, and the weight of all the classic music he’s recorded makes you raise your game somehow.” The album’s lead-off single, ‘This Ain’t A Scene, It’s An Arms Race’, charted at #2 in the UK, a near-perfect synthesis of R’n’B squelch and punk-rock furore indicative of the ambitious, unabashedly pop-friendly embrace of Infinity On High.

A knock at Stump’s door signals the next in the day’s packed series of events, playing blackjack in the casino of the Palms hotel with contest winners from a local radio competition. With fans milling about the hotel hoping for a glimpse of their heroes, Charlie and his security detail ferry the group into the casino like a crack commando unit. But as the group take their places at the card tables and meet the competition winners, few in the casino seem to care, too enthralled by the endlessly blinking and chirping slot machines swallowing their cash at fearsome pace. Welcome to Vegas, baby. The gambling session is followed by another meet’n’greet in a ballroom on the other side of the hotel, the security guards marching the band over so they can have their photos taken with fan-club members who bring ‘FOB’-decorated cup-cakes and plush animal toys for their heroes.

Minutes later, the group are onstage, dashing through their anthems of adolescent heartache with joyous energy, Wentz and Trohman leaping off an onstage ramp and throwing rock shapes as the audience responds with that same Beatlemanic roar from earlier. An impressive cover of Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ is momentarily curtailed while Wentz cools off a fight brewing in the crowd. Panic At The Disco’s two frontmen take the stage for a surprise acoustic set before Fall Out Boy’s encore, which closes with an explosion of pyrotechnics and glitter, and more of those teenage screams. (Wentz points out earlier that the Vegas show is at a much smaller venue than the rest of the tour, precluding such onstage FX as the props which malfunctioned earlier in the tour, leaving Patrick Stump trapped inside, much like Spinal Tap bassist Derek Smalls.)

Moments after he’s run offstage, Wentz takes time out from an impromptu aftershow party brewing backstage with his friends from the other groups touring with Fall Out Boy during the summer, returning to his bus to talk some more, about a future he once couldn’t see, and his rejection of depression and self-medication as a way of life.

“This had become a business of misery by accident,” he smiles. “The whole idea of the new album was to have a smile on your face, that you shouldn’t feel guilty about being happy. I love the adventure of being in Fall Out Boy. Sometimes I think about homeless guys, and about how I could easily find myself in the gutter someday – that’s just the kind of personality I have – but it would still be an adventure. I’ll be talking to Hobo Jim on the boxcar, saying ‘Yeah, I was in Fall Out Boy, I hung out with Jay Z!’ And he’ll be like, ‘yeah right, the guy in rags hung with Jay Z, sure man’.”

For all his fantasies of unexpected hobo-dom, Wentz is unlikely to find himself homeless in the near future, and seems to have made some kind of peace with these newfound responsibilities of fame. “I’ve got a weird brain chemistry, he admits. “Honestly, I used to wake up and wanna blow my head off. I don’t feel like that anymore. For so long, my life was like the crocodile with the clock in his stomach chasing Captain Hook; the clock always ticking and the jaws always snapping. There was a good six months where I was just toxic, over-medicated. I’m relying on that less, relying on my friends more. I think last year was the most dangerous year for Fall Out Boy, and the most dangerous year for myself, because its so easy to believe the people whispering in your ear, to get caught up in it all. I thank God I got through it, and came out of the other side.

“I picture myself having a family now,” he smiles. “Before, my dreams were about being in the biggest band in the world, playing shows all over the globe to thousands of people. Now, my dreams are of back yards and hanging out. It’s a good progression for me, trying to figure out what’s normal…”

Hemingway, gnawing at a juicy marrowbone on the floor, jumps up into his master’s lap at a click of Wentz’s fingers, Pete tugging lovingly at his ears, so the dog playfully bares his fangs. “Anyway, I’ve got Hemingway now,” he laughs. “I can’t just sleep in past noon anymore, otherwise he won’t get fed.”

(c) 2007 Stevie ChickSaturday, September 08, 2007

my... disk... drive... is... dead...

Am deep into a weekend of writing and transcribing, and going slightly mental. Earlier I fashioned a relief sculpture of E.T. the Extra Terrestrial from an old clump of Pritt Tak attached to my speaker. Now, I am several hours into transcribing an interview tape, and have hit a gloopy stew of self-congratulatory wank from my subject. "We cannot fail, because we're so talented, so passionate, so focused, so committed..." He goes on and on, as does my typing, small bones dislodging specks of cartilage and playing croquet with them through the fleshy tunnels of my fingers. CLACK/THWACK/CLACK/THWACK. "We're so good, so fucking GOOD," he continues, and I'm thinking about arthiritis and how, when I can no longer type, because my hands are but twisted claws, it'll have been the fault of said rock star and his endless blether of banal self-love.

Thursday, September 06, 2007

The Drips

The Barfly is the biggest cheese of all

“You know what, man?” grins Matt Caughtran, The Drips’ sweet, dough-faced frontman, “That was the raddest thing ever. I love those dudes – because I’ve always been one of those crazy dudes. To have guys like that show up really means something – when dudes who listen to GBH 24 hours a day are coming to your shows… It’s not like The Drips are a hardcore band, anyways…”

Perhaps not when placed next to GBH, but The Drips’ breakneck punk-rock plugs deep into the more melodic vein of SST Hardcore (Husker Du, Descendents), their flab-free pop – played out on swaggering metallic guitars, nailed down by machine gun snares and illuminated by Caughtran’s kerosene-doused bellow – very much a sunshine-flip to Caughtran and guitarist Joby J Ford’s day-job in steroidal thrash-punks The Bronx.

“It’s sort of a ‘circle of friends’ thing,” smiles Matt, unthreading the groups’ tangled family trees. “Vince and Dave (bassist and drummer, sons of Los Lobos guitarist David Hidalgo) were childhood friends with Joby, and he played in their group. I joined, and we became the Drips. Then Joby and I started writing songs that didn’t really fit with the Drips, and that’s how The Bronx started.”

The Drips hit the back-burner while The Bronx rode the success of their self-titled 2003 debut, a brutish rush of shrapnel guitars and deadly dynamics you really should own. When the pressure of recording the follow-up, their first for a major label, began to tell last year, Matt and Joby were glad to blow off steam with The Drips.

“The new

Which is where The Drips came in. Re-ignited, they added Distiller Tony Bradley on second guitar, dusted off the songs they’d written six years before (and wrote a couple of new ones) and got into the studio. The result - a blistering eleven-song amphetamine-ripped dash - is gloriously kinetic noise candy, tunes painted in frazzling neon guitars as Matt howls along as if ‘Oi!’ were the sweetest sound he ever heard. “The

Examples of The Drips’ unabashed pop sensibility include interpolating a slice of Men Without Hats’ 80s New Wave hit ‘The Safety Song’ into careering closer ‘Coastline’, drubbing Matt’s vocals with dubby echo on the lightning-strike ‘Downbrown’, so his voice scars audible traces into the galloping melee, and ’16, 16, Six’, the group’s ballad. Unfolding to a sugary skank The Police would’ve approved of, it’s a Teen Love story that’s honestly awkward, clumsy, painful - not unlike Teen Love itself. Judging by how the screamo boys yelled along to lyrics like “This is the story of a broken heart / I tried to love but it fell apart”, striking heroic poses like they were some sozzled divorcee singing ‘I Will Survive’ at Karaoke, it could make The Drips huge.

“If it sounds awkward and naïve, that’s because I wrote it a long time ago,” offers Matt. “It was the first love song I ever wrote, and it was about my first girlfriend, who I was with for seven years. It was a tumultuous relationship.”

For all their phosphorent ferocity, The Drips onstage are mostly defined by Caughtran’s amiable, excitable charisma, grinning non-stop, like every moment – sharing his mic with the moshpit, leaping into their out-stretched arms – were his best ever. Which is pretty much the truth.

“Shit yeah, man,” he affirms. “The

The Grates

Lost in West London late one night during their first an masse trip to England, aimlessly wandering foreign, unfamiliar streets, The Grates happened upon a parked car by the kerb, disco music blaring, its lights on, an ungentle a-rocking occurring. Peering deeper into the urban undergrowth, they made an unsettling discovery: the passengers therein were engaging in proud, loud and lusty congress on the backseat.

“All the windows were fogged up, except the wound-down one we could see the arse through,” grimaces John, their very hairy guitarist, still somewhat bemused.

“We were all like, wow.” adds singer Patience, her eyes wide (but they’ll go wider still, later). “That’s bold. That takes guts.”

It is now the grave responsibility of your correspondent to explain to Grates the infernal practise of ‘dogging’, thus divesting them of their cherished innocence, perhaps FOREVER. It isn’t pretty.

“You mean,” whimpers drummer Alana, disgust etched on her face, “They wanted us to join in?”

“I have this ongoing belly problem going on. I don’t know what the story is, I think some parasites might be in my guts…”

Patience leans across our table at the Electric café in West London, and peels out a grin so wide her eyelashes tickle the corners of her lips. You or I might, perhaps, greet such knowledge with an expression of dismay or upset, maybe with the word “Bother” or some vague synonym. Patience seems excited, elated by this news. To be honest, Patience seems excited, elated by petty much everything, a naturally heightened state of excitement that translates so well onstage, as she leaps and stamps and twists across the stage, insane grin in place, a little breathless (but we’re not sure if she’s ever out of control).

This sunny disposition, this heady lust for life, pervades the Grates camp. They are, declares the winsome Alana, “The very best of friends. We even stay in the same hotel room, all three of us, when we travel.”

“We argue all the time,” adds Patience (such an ill-fitting name - her every atom seems to buzz with impatience, for all the stuff there is to do and all the fun there is to have). “Our band practices take place in John’s Dad’s shed. We play for half an hour. Then we go and eat some barbecue…”

“Then John’s mum comes downstairs, and we have a chat,” continues Alana. “Then we surf the internet for a bit. Then we have an argument. I leave the room for a bit, and then come back, and we all make up, and play for five more minutes to celebrate. We’re all the best of friends,” she says again, “So we can afford to wanna kill each other one minute, and then all share a hotel room the next.”

“I taped part of our rehearsal the other week,” adds John, grinning with a simian wickedness. “All that was on the tape was Patience wailing, ‘I’m never gonna write another good song again!’”

She’s already written several wonderful ones. The Grates’ debut double a-side is a case in point; ‘Message’ skips and stomps like these suburban kids are taking a glitter-daubed chainsaw to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ blueprint and dancing gleefully in the wreckage, a tumbling racket of revving guitars, tumbling drums, stop-start noise and Patience’s howl, ricocheting off the speakers like a squash ball.

The flip is even more charming. ‘Suckafish’ is odd, off-kilter, faintly celtic but owing more to pixies at the foot of the garden than any leprechauns. It has that lumbering, gentle heaviness you always get when typically-loud musicians deign to decrease the volume, a sweet and messy thing of vulnerability and sing-song poetry that recalls a beautifully bruised Belly. You don’t expect something so tender to be hiding underneath something so brattily brash.

We aren’t here to talk about the music really, though, or at least that’s what The Grates seem to believe. We talk for about 90 minutes, all in. I don’t ask a single question. The tape clicks on while they’re talking, and whirrs absently as the chat unfurls, of wild and arcane subjects. Like what their spirit animal would be.

“Patience’s spirit animal is the seal,” explains Alana, authoritatively. “And Jon’s spirit animal is a bear. I don’t know what my spirit animal is.”

“It’s a toss-up, with Alana, between a polar bear and a koala bear,” interrupts John.

“I don’t feel an affinity with any animal,” frowns Alana. “And that’s my spiritual crisis.”

“John’s a bear, because he’s so very hairy,” offers Patience.

“And because he’d love to be able to hibernate,” adds Alana.

“I don’t think I could manage it, but I’d love to try,” smiles John. “Sleep for a few months, get it all out of the way, and then work for nine months without sleep.”

“John, bears still sleep at night when they’re not hibernating!” snaps Patience.

“Yeah, they only hibernate in the winter because there’s no food for them to eat.” adds Alana, scarcely more gently.

“Oh,” replies John, his eyes drooping slightly, so he looks like a momentarily glum (yes!) bear.

Check out the Grates’ website and you’ll be greeted by the band’s DIY design aesthetic in full flow, a cut’n’paste glut of vibrant colours and affectionate scribbles and paintings. The band press up their own badges, design their own sleeves, do everything, in fact, because they enjoy it. That’s the only reason they do anything they do. Luckily, the Grates enjoy being the Grates a great deal.

They formed in their hometown of Whitchurch, Brisbane, having been friends for as long as they could remember. They were, by their own admission, ‘rubbish’ to begin with, until Patience went off to live in London for a while, returning with a much stronger voice than before. The Grates are burgeoning huge in their home country, beloved of influential radio station Triple J. They deserve to be massive, everywhere. But especially places with decent air-conditioning.

John: “Its so hot in Australia, and I sweat so much when we play.”

Patience: “John’s a hairy guy…”

Alana: “But the venues in Australia rarely have air-conditioning. I’ve gotten so hot I’ve felt I might pass out while playing…”

John: “I’ve had sweat pouring off all of my body! Rivers of sweat!”

Patience: “I’ve thought, maybe I might puke onstage! And I have felt like it.”

Alana: “We discuss it beforehand, if she thinks she might get sick, we have a bucket onstage for her.”

Patience: “Because that’s cooler than saying, ‘Aw, I feel sick, I have to stop rocking out now!’ I’m not a baby…”

John: “Dad’s shed is air-conditioned, its excellent. We wouldn’t have gotten anything done without that. We don’t write fast songs during the summer; we write them in the winter, to stay warm!”

John’s Dad’s shed is the Grates’ HQ, the clubhouse where they hatch their plans for twisted nursery rhyme-aided world domination.

Alana: “It’s awesome… it’s huge, it’s soundproofed…”

John: “It’s not entirely sound-proofed. I walked outside it once while Alana was playing drums, it was really loud.”

Alana: “But the neighbours don’t complain. Our next door neighbour is insane, and she’s really lovely, and she just really enjoys tracking the band’s progress!”

“We’d been eating at this Chinese place,” continues Patience later, on her digestive disorder, “and I ordered ‘vegetarian’, which was disgusting, like raw tofu floating in chicken stock. Whatevs!” she snaps, efficiently shortening a sarcastic ‘whatever’ to two syllables. “So I ate some of John’s noodles, which he had with the pork. It was a skanky restaurant, and before we got served, I kept joking to John, ‘You know what meat they’re serving?’” Patience points at her handbag, emblazoned with a big picture of a cat. “And I’m hella allergic to cats. I reckon some cat-meat touched the noodles, and I had an allergic reaction on my insides. I’m allergic to everything about cats: their saliva, their hair…”

“And now, it turns out, their meat too!” laughs Alana.

“And my body flllllllllipped out” - ‘flipped’, but with the ‘l’ drawn out for, like, 5 seconds. “Whatevs, it was the most disgusting meal ever, and it was cat. Whatevs.”

(c) Stevie Chick, 2005

Saturday, September 01, 2007

Monday, August 27, 2007

Roots Manuva

The setting is Pimlico school, Westminster, in the mid-1980s. "Hip hop was everywhere, everybody was writing things on their tracksuits and colouring their white trainers black, having freestyle battles on the concourse," reminisces Rodney Smith, aka Roots Manuva, aka British Hip Hop's Brightest Hope. "It was like the hip hop school, huhuhuh!"

And so it was that young Rodney was bitten by the hiphop bug - then written off as some flitting fad - as it swept through the UK's nightclubs and playgrounds. "I tried break dancing. I even tried scratching, totally wrecked a lot of records. I thought you were supposed to drag the needle across the record ... Sorry, Mum! It was something I loved, but I never imagined it would pay my rent. It never felt like something I could be a part of."

Ironic words, considering Roots Manuva's new album, Run Come Save Me, proves that hip hop is no longer an exclusively American culture but an international language encompassing a thousand tongues, including Rodney's London accent and his Jamaican roots. Whereas previous British rappers have been scuppered by their parochialism, he has taken the loose, mix 'n' match cultural identity of contemporary London and created an album that sounds global .

Roots, now 28, draws as much on the sounds of Brixton - dancehall reggae, skronky techno and smoked-out dub - as American funk and rap. Like Tricky, like Muslim agit-rappers Fun'Da'Mental, like 1970s ska-punks The Specials, his music celebrates Britain's unique, messily integrated eclecticism better than Robin Cook's clumsy tikka masala metaphors ever could.

"I'm a second-generation UK black, just trying to find his feet, spiritually and economically," he says. His lyrics are complex and spiritually troubled, and the question of identity is a key theme. "I'm just trying to make sense of this Roots Manuva character," he laughs. "Where Roots ends and Rodney begins."

His parents, immigrants from Banana Cove in Jamaica, were strict; his father is a Pentecostal deacon. A career in hip hop, Roots remembers, "was not something they encouraged; it was something they discouraged". And yet many MCs - from Fugees's Wyclef Jean to Mos Def - come from religious backgrounds, swapping preaching for another form of oratory.

The transition isn't so simple in Roots's case, however; moral turbulence courses throughout Run Come Save Me. Track after track finds Roots tussling with religion, spirituality (pointedly two separate things to him) and guilt.

"If I'd had parents who were really into music, who had a massive record collection, I don't think I would've been so into music," he says. "That I had to go next door to hear the latest reggae tune, or that our parents wouldn't take us out to the cinema or to the arcade, made me really appreciate it when we did do those things.

Have his parents accepted his lifestyle choice? "Yeah, they're cool. They still can't believe I'm making any money from it. They always ask: 'Why aren't you on Top of the Pops?'" And he really should be. Last week, when his sublime Witness (One Hope) single entered the UK charts at 45, Atomic Kitten were at number one with their insipid cover of Eternal Flame.

Which is a better representation of modern young Britain? Yet Roots is sanguine about the mainstream culture that has yet to embrace him. "Radio is all about midrange frequencies and melodies, and Witness isn't too melodic. It's harsh."

But he is convinced he's part of a burgeoning revolution. "There's a whole brand-new class, people in music and the arts and sports ... a new uneducated middle class. We're shopping in Marks and Spencer and using balsamic vinegar, but we've got no GCSEs, no A-levels and no degrees.

"Technology is changing everything," he says, and he should know. He just bought a DVcam so he can make his own movies. "They're just abstract art movies at the moment 'cos I can't work the camera properly. Maybe I should go to one of them weekend courses that teach you how to be the next Steven Spielberg."

Or maybe he could just continue being the first Roots Manuva.

(c) 2001 Stevie Chick